What is ruinous empathy?

A plea for lived self-empathy in leadership

Empathy is on everyone’s lips: The other day I received a fascinating impulse regarding ruinous empathy in a corporate context from my colleague Lara. The employee is highly qualified, creative yet at the same time very frustrated. Why? Because she wants to develop her professional skills. She has been working way below her abilities for a long time and has already applied for other in-house jobs several times – so far unsuccessfully.

Although she did have what she thinks a really “nice” conversation with her supervisor in which she asked for support for the internal transfer and had felt understood, Lara has now handed in her resignation after all. The reason: the lack of support both from her superior and from the HR department as well as the poor development opportunities in the company. With that, the company loses an excellent employee. How did it come to this? Is this perhaps a case of ruinous empathy? And what would empathic, sincere and appropriate leadership behaviour have looked like? We’ll resolve this question in this article.

Empathy is all the rage nowadays. It’s supposed to promote an appreciative togetherness and overcome the ailing corporate culture with all its accompanying symptoms. Companies wanting to remain sustainable just hand out a packet of “Empathy Forte” to their leaders and the problem is history. At least in the case of Lara’s supervisor, that would certainly have been helpful, don’t you think? But like any remedy, it can also be overdosed or even become ineffective. Empathy experts such as Dr Karim Fathi and Herbert Haberl therefore also speak of the empathy paradox. This means: the pressure of the performance and consumer society on leaders is rising while at the same time everyone is clamouring for more empathy, which we, however, don’t find easy to show under pressure. Crises such as the pandemic, the consequences of war and the accelerated digital transformation therefore even inhibit empathy for many leaders.

Even if empathy, with good reason, is hyped as a reliable active ingredient in leadership, I claim that empathy alone cannot suffice. To facilitate diversity, acceptance and thus appropriate management behaviour and to promote a healthy corporate culture, it’s indeed necessary to team it with other active ingredients.

What I mean by this, what understanding of empathy is at the basis of this article and what this has to do with swimming, I’ll cover below. With this article, I want to draw a realistic picture of what empathy can or cannot deliver and what leaders can do to emancipate themselves from the pressure of empathy.

What empathy can do – and when it becomes ruinous

In the management context, as well as in the social sphere and in marketing, the term “empathy” has become a trendy word over the last three decades, which conjures up positive connotations at first.

But in fact, we have a distorted image of empathy and underestimate that it can also become ruinous and unhealthy.

Here are a few aspects or, if you like, “active ingredients” that in my opinion are often lacking in the empathy discourse: First, the capacity alone isn’t sufficient, there must also be the willingness to use it, that is, to really empathise with the other person. Which leads me to the second point: Empathy, attended by keeping things under wraps, can become ruinous. Ruinous empathy, according to Kim Scott, is when, for example, colleagues feel connected to one another, but the critical issues aren’t addressed, i.e. there’s a lack of candor. Criticism is on the tip of our tongue, but we gloss over it instead for fear of offending the person’s feelings. If the worst comes to the worst, this leads to the person working below their possibilities being sacked. And, naturally is completely taken by surprise because the employee has been left in the dark all this time.

A third crucial ingredient, is self-empathy. As a leader, I cannot be sincere and empathic if I don’t know and understand my needs and act accordingly.

Furthermore, cognitive scientist Fritz Breithaupt for example argues that empathy with others can also be a prerequisite for targeted humiliations and cruelties. Paul Bloom, professor of psychology at Yale University, in his book “Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion” (ed. Vintage, 2018) even advocates the abolition of empathy in favour of skills such as self-control, reason and a broader compassion.

Being empathic with others doesn’t necessarily go hand in hand with appropriate behaviour from leaders. Moreover, it’s difficult to feel empathy for a crowd of people because we only have capacity for a few, usually our loved ones. If this limit is exceeded, we may even experience empathic stress.

The good news is that there may be something more sustainable than pure empathy in everyday leadership. But more on this later. Let’s take a closer look at the term first.

What is empathy

According to the current Duden entry, empathy means: the willingness and capacity to empathise with the attitudes of other people. The corresponding Wikipedia entry elaborates even further: empathy is the capacity and willingness to recognise, understand and act appropriately on another person’s emotional state, emotions, thoughts, motives, and personality traits. In my opinion, this is where it already starts to get vague. This article will show how important it is to distinguish between the ability and willingness to empathise and the willingness to “act appropriately.”

But first, I would like to make room for a third definition, namely the empathy understanding of non-violent communication (NVC), which was coined by the founder of NVC, Paul Rosenberg. Empathy, according to NVC, accepts what is and makes unbiased room for everything that wants to be heard. The following section, too, is close to this understanding.

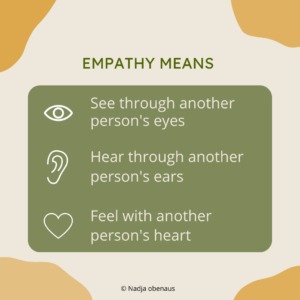

Empathy is feeling with the entire body

Empathy also occurs on a physical level. Facial expressions and gestures play an important role. Empathy means being able to see through another person’s eyes, hear through another person’s ears and feel with another person’s heart.

The so-called mirror neurons are mainly responsible for the fact that we can empathise with observed feelings. It’s also thanks to the mirror neurons that we intuitively imitate an observed behaviour and – in the case of sympathy – align our body in the direction of our counterpart, thus imitating them. We therefore unconsciously swim on the same wavelength and are in tune with each other:

Spektrum’s encyclopedia of psychology also refers to the term “empathic resonance,” which describes the resonance of feelings or thoughts with other people. If someone hits their finger with a hammer, for example, we suffer affectively, so to speak. The extent to which we resonate empathically is always also shaped by our social experiences and experiences in the social context.

Empathy, therefore, is something very physical and, eventually, it is attention with all the senses. We show our care to our vis-à-vis not only by paying attention to them mentally, but also by turning our nose and navel, i.e. the body’s core, towards them. For the purposes of including the body in this article, I offer the following exercise:

Exercise for sincere empathy in everyday life

You can either write your name on your forehead or use a sticky note to place it on your forehead for others to see. In which direction or for whom did you draw the letter? Did you write it for yourself or for others to read? The answer is completely non-judgemental. However, it demonstrates how close we are to ourselves or to others.

ALSO, turning your nose and navel towards the other person more often, and just listen while the other person pours out their heart, is of course the best practice.

What empathy is not

Empathy (alone) is not a panacea for successful cooperation, for a sustainable company or against employees who leave the company.

It is nothing but the ability and willingness to tacitly empathise with others. Empathy alone, however, is not enough to fulfil the leadership responsibility in a complex environment under pressure or to create added value.

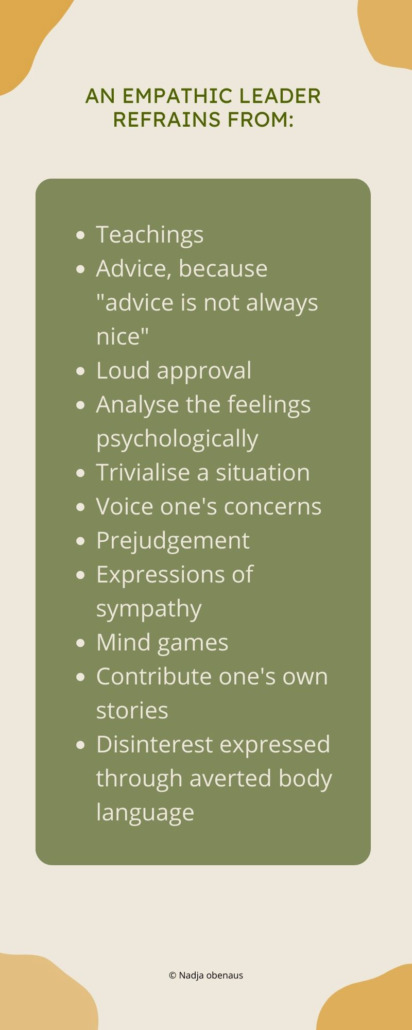

An empathic leader refrains from:

- Teaching and advice because “advice is not always nice”

- Analysing the feelings psychologically

- Trivialising a situation

- Voicing one’s concerns

- Prejudgement

- Expressions of compassion

- Mind games, etc.

- Contributing one’s own stories

- Disinterest expressed through averted body language

The list of inappropriate reactions is long.

Instead, it helps to reflect “What would the person in the situation have hoped for? What would I have wanted myself in that situation?” Because that’s what “empathising” really means.

To react to improper action, radical self-empathy is of vital importance. For as indispensable as it is to recognise and understand the feelings and needs of other people, it is well-worth applying the same to ourselves!

Let’s recall what was said above: there are three steps. In order to 1. recognise, 2. understand and 3. act (appropriately), it is necessary to care for yourself first. And this is where self-empathy comes into play.

Self-empathy as the foundation for empathy

“Am I even adequatly “empty” to be there for someone else or am I carrying too much around with me currently?” If the answer is “no”, it is important to take care of ourselves first. Especially in times of crisis, we quickly lose sight of ourselves and neglect our needs, which also implies that we aren’t good at being there for other people and empathising with them.

Exercise for more self-empathy

A good exercise to train your self-empathy muscle derives from the exercise for self-empathy of the magazine “Neue Narrative” (in German).

Recall a situation when a respected person was feeling low – maybe because the person did something wrong. What did you offer or say for comfort and how did you say it? Now think of a situation in which YOU were struggling with something. How did you deal with it? What words did you use? Just embrace it and breathe. And accept all the feelings that are stirred up. Now take a few minutes to write down the perceptions, feelings and thoughts that came up. By doing so, you reinforce the effect.

Only those who are able and willing to be compassionate with themselves can take the three steps of recognition, understanding and acting with others. If someone is drowning, and you jump into the water to save them although an injury makes swimming impossible for you, you’ll drown with them, right?

For a start, it’s a good idea to “swim free” from emotional stress. Does that sound weird? Just to a certain extent. I’ve been a keen triathlete for many years and have realised that you can learn a lot about self-empathy during swimming training, which is why I’m mentioning it. Swimming addresses the entire body and has a beneficial effect on the mind. As with other sports, swimming initiates the release of endorphins. Stress reduction and relaxation are the beneficial consequences. As you know, sport also frees the mind – this holds particularly true for aquatic exercises.

For many triathletes, swimming is the discipline they dread the most as it’s where they’re short on experience. Understandably so, since very few of them were lucky enough to attend a swimming course and learn to swim in their childhood – and then they struggle with it in adulthood. It’s almost the same with self-empathy.

Unlike self-criticism, self-empathy, doesn’t ask you what is wrong with you or what needs improvement. This is an aspiration that is deeply rooted in the heads of many bearers of the meritocracy who obsess about self-improvement. Self-empathy on the contrary simply asks how I feel and how I can accept what is. That’s precisely what requires a little training. Whether it’s swimming training or empathy training, that’s up to you.

Self-empathy, like empathy, has limits that are very individual, but they are crucial to stay healthy. By the way, being able to consciously set boundaries and withdraw attention from another person is a clearly underestimated quality called ecpathy.

Less empathy is sometimes more: How ecpathy can help

The ability to actively exclude feelings where appropriate is called ecpathy. It isn’t exactly the converse of empathy because no one who isn’t empathic, can automatically be considered as ecpathic. In fact, ecpathy describes a useful counterpart, the antagonist of empathy, without which the empathic muscle cannot return to its former strength. Ecpathy can help leaders in emotionally stressful situations to actively distance themselves. Again, this can be practised.

Exercise for more ecpathy

As described above, empathy wields a great influence on a physical level. You can also practise ecpathy by involving the body. If you clearly want to distance yourself in conversational situations, it’s helpful to position one foot rather centred (with you) and the other with your counterpart; this also creates inner distance if you are in danger of empathising too much.

Alternatively, objects like a jewel can also be useful to consistently realise our boundaries in conversations. And they act as a reminder to physically and also communicatively pull ourselves out of a situation that is getting out of hand emotionally.

When this situation occurs, it often helps to ask the other person for a short break. You’re welcome to try it out!

I’ve already described amply what empathy is, what it is not and what helps to exert self-empathy. In addition, I have already indicated that empathy can also be unhealthy and introduced the concept of ecpathy to protect us from emotional stress.

Too much of a good thing: When empathy becomes ruinous

But there’s another level where empathy is paired with a behaviour that is “unreasonably” passive and thus becomes ruinous. This happens when empathy doesn’t translate into appropriate action, but even results in silence, or if the worst comes to the worst in denial of assistance. Let’s look at the case of my colleague Lara again. It’s obvious that Lara left because she felt understood but not supported in any way by her supervisor. What’s more, her supervisor didn’t fulfil her leadership responsibility – to act in the interest of the company. An empathic leader turns towards, recognises needs, or listens silently and, moreover, takes good care of herself. Only radical self-empathy can resolve the empathy paradox.

Then self-empathy is followed up by candid action. Even if it’s “only” to get another leader on board because one’s own batteries are quite low at the moment.

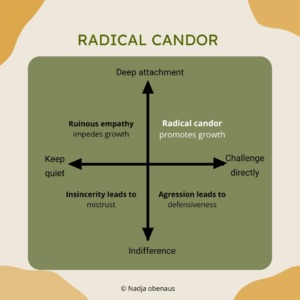

In Lara’s case, we don’t know exactly what gave rise to her supervisor’s lack of empathy or sincerity. In this case, there are several scenarios that could explain why empathy can become “ruinous”, which I would like to go through here. Both the degree of attachment and that of sincerity play a part.

- The person is too attached to and too afraid of hurting their vis-a-vis that they slide into avoidance or even pity.

- The person is too self-absorbed, or isn’t “empty” enough to really engage with the needs of the other person with all their senses.

- The person keeps important things under wraps rather than addressing them and thus wastes development potential.

- The person doesn’t feel connected enough to the other person, assumes indifference, or makes up lies or beats around the bush.

- Another extreme is that the person becomes disconnected and brutally honest or even offending.

Room for manoeuvre: Radical candor

All of these scenarios are extremes, and it could well be that in Lara’s case, there were several things going on at the same time. There’s room for manoeuvre between brutal honesty and manipulative hypocrisy, between inexorable command and excessive consideration for sensitivities, between self-pity and ego trip. This calls for a combination of different actions or active ingredients: clear messages in lucid and friendly words – specific and sincere, respectful and empathic – with an eye to the feelings of the counterpart while at the same time maintaining one’s own boundaries.

A concept that realistically follows this combination is “Radical Candor” by Kim Scott. She presents the basic idea in a graphic with two axes.

And what if we’re unable to be empathic and sincere ourselves? Then there’s always the possibility of involving colleagues or outsiders, as shown in the following exercise.

Team exercise: Peer consulting

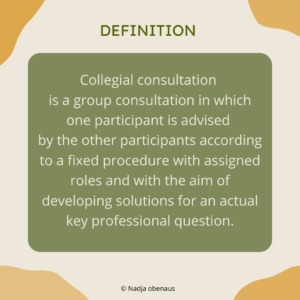

A proven method to run through different scenarios for appropriate behaviour and thus develop solutions is peer consulting. Collegial consultation is a good way to tap into the potential and knowledge of a group in a solution-oriented way. Different experiences, a change of roles and new perspectives facilitate looking at problems from a different angle and solving them differently.

Peer consulting can also be conducted virtually.

By the way: There are many situations in which it is worthwhile to consider how to address something in advance. Expressing the message clearly and showing consideration for the other person’s feelings have to be carefully weighed up. For inspiration, I warmly recommend the new book by Isabel García. In “Wie sage ich eigentlich?” (How do I actually say it?), she provides 30 communication tips for dealing honestly with yourself and showing appreciation for the other person – both in the private and working life.

Go for a swim, connect and call things as they are!

Paying attention to oneself empathically and clarifying one’s own needs is the basis for empathic cooperation and a healthy corporate culture. A culture that allows room for conversations and co-creative problem-solving for the company.

Only when we as leaders have shown enough self-empathy are we potentially willing to devote ourselves to problem-solving. It’s not until then that a basis is created for empathic and sincere resonance with our colleagues. Therefore, it’s not surprising that we can be less empathic with someone we don’t know and more empathic with people close to us. We care about their well-being, their satisfaction, and their growth. And that is the difference to ruinous empathy, which in a corporate context can impede growth by keeping quiet.

As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, there’s something far more sustainable than an empathy “pill”:

I’m referring to the interaction of self-empathy, empathy (attachment) and sincerity. If we care for ourselves first and see with the other person’s eyes, hear with the other person’s ears and feel with the other person’s heart, i.e. feel connected to the other person and directly address what bothers us, then we can succeed in maintaining sustainable relationships and promote growth. Because appropriate behaviour by leaders through radical attention facilitates healthy growth – the basis for the sustainability of every company. On that note, happy disconnecting!